Oral History no.1

"Across Main Street: Race, Religion, and the Ocean Grove Divide. Linda Alligood-McLeod’s Childhood Experience.”

Listen to her story.

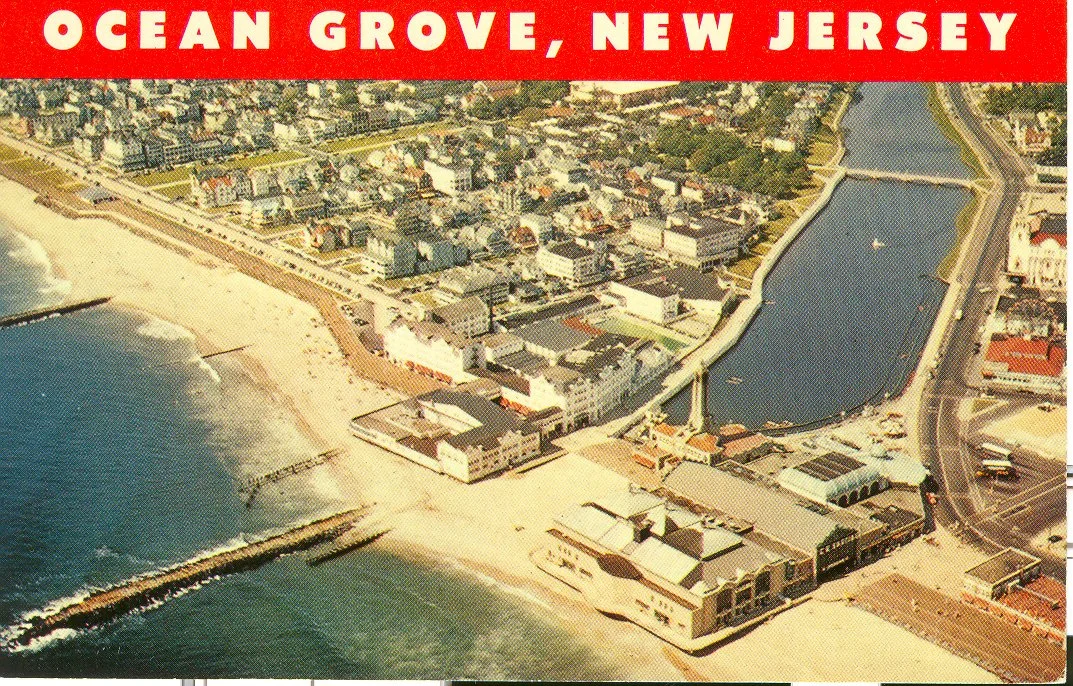

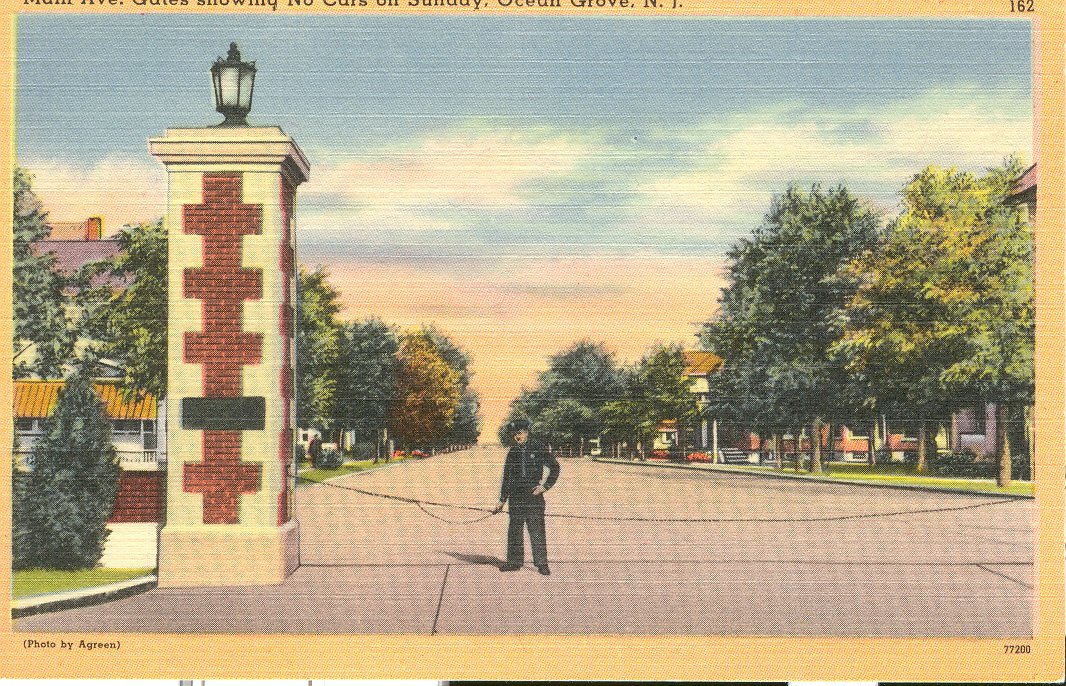

In this oral history interview, lifelong Ocean Grove resident Linda Allgood-McLeod reflects on her experiences growing up in the tight-knit, predominantly white Methodist community of mid-20th-century Ocean Grove, New Jersey. She recalls an idyllic childhood marked by safety, familiarity, and neighborhood watchfulness, but also by exclusionary practices that barred Black and non-Methodist families from owning homes. Linda candidly discusses moments that revealed racial prejudice, from the rejection of her parents by a committee, and being told to stop playing with a Black neighbor boy. She recounts witnessing the slow integration of local schools, the racialized labor of Black summer workers at seaside hotels, and the tensions surrounding the 1968 Asbury Park riots—during which she was dating the man who would become her husband, a Black resident of Asbury Park. Reflecting on later decades, she describes the town’s shifts—from deinstitutionalization and boarding homes to the arrival of the gay community and gentrification—contrasting today’s affluence and anonymity with the close, if insular, community of her youth.

Transcript:

Melinda: Today is September sixth, 2025. I'm Melinda Allen-Grote, and I'm meeting with Linda Allgood-McLeod at her home at Heck Avenue in Ocean Grove as part of the Historical Society of Ocean Grove's Oral History Project. So thanks for agreeing to participate. You know this is about Ocean Grove.

Linda: Oh, I do.

Melinda: So tell me what it was like growing up here.

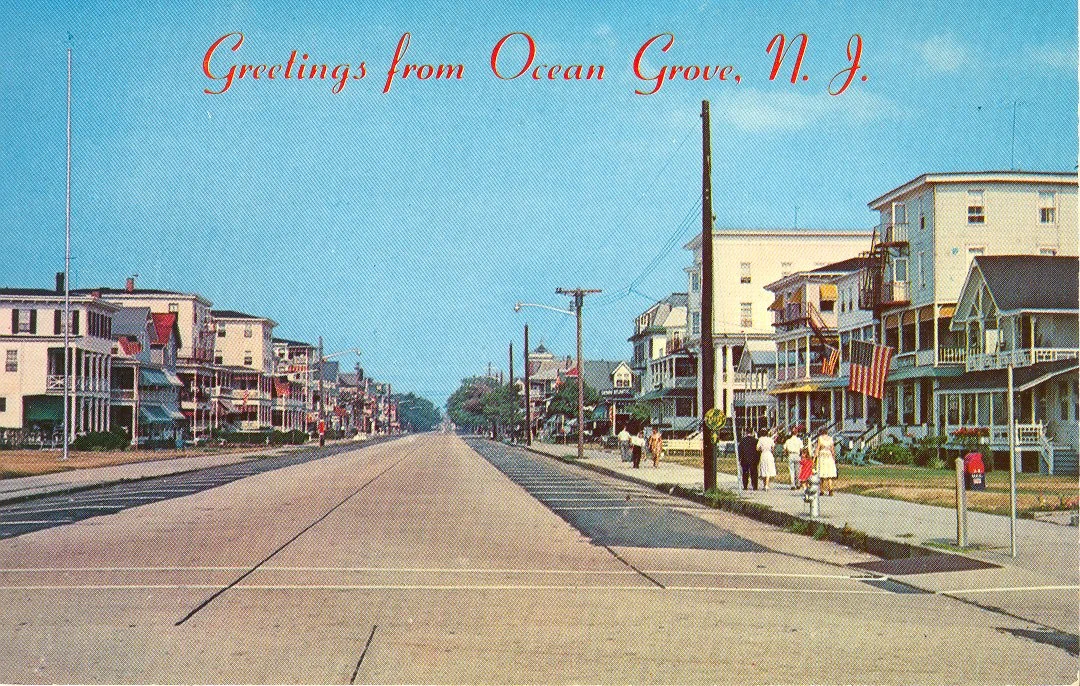

Linda: It was a wonderful place to grow up. Ocean Grove, it was a perfect place. If you were a white Methodist or a child of white Methodist parents, it was probably a perfect place to grow up. It was crime-free. We left early in the morning. You came home at five o'clock for dinner. Your parents had no idea where you were. It didn't matter because you never went down a block where you didn't know someone on the block who was watching out for you.

Melinda: Tell me more about that.

Linda: All right. My fourth-grade teacher lived two houses down. If I did anything in school, good or bad, she would tell my mother as she walked past the house. You don't have that today in education. Teachers, first of all, wouldn't be allowed to be that familiar. She thought nothing of giving my mother a report on my sister and me. So you just knew. Everybody knew everybody.

Melinda: So let me go back to something that you said right at the beginning, that if you were Methodist and white, it was a perfect place to live. And if you weren't?

Linda: You couldn't live here. You weren't allowed. They kept non-Methodist out by making you join the Methodist Church in order to buy a house here. And you also had to go before a committee. And shortly before my parents bought this house from my grandmother.

Melinda: In what year?

Linda: I want to say 52, but I'm not... Yeah, 52. They bought it from my grandmother.

Melinda: Who had been here for how long?

Linda: I honestly don't know. Maybe 10 years or so. Because she lived on Webb Avenue for a while. Then she and her husband bought this house. Then he died. My mother moved in with her because she had a special needs son. I had a special needs brother at the time. They moved in with my grandmother mother to help out because now she had twins and a special needs son. But they had to meet before this committee in order to move into here. They were rejected at first because it was reported they had been at a party and brought us to the party where alcohol was served. So they were declined. But then they had so many friends in Ocean Grove that they were allowed to move in. But this was how they kept black people out. They They would never even make it in front of the committee. So everybody we saw was white. You didn't see diversity. With the exception of my brother, the school sent a tutor. When Karen and I were five years old, they sent a tutor to the house to work with my brother, Mrs. Gill, who was black, and we hadn't seen black people before. I remember thinking, 'What is she doing in my house?' 'Why is she here?' And embarrassingly enough, I once asked my mother, "Was she allowed to use our bathroom?" My mother was highly offended and said, "Why wouldn't she be?" That was a wake up for me, but I haven't seen black people in Ocean Grove. I was totally surprised that Mrs. Gill could not only come in, she would drink out of glasses and use our bathroom, but she was wonderful. She got my brother. She took care of my brother. She tutored my brother.

Melinda: Were there any issues in the neighborhood about her being here?

Linda: I don't think If so, we were too young to hear about it. I mean, I can tell you some issues in the neighborhood later on as we got a little bit older. But no, and I think it was probably because everyone knew my brother. For a special needs kid, it was a great place to grow up. Ocean Grove was so tolerant of people. As long as you're white, that's what it is. They were so tolerant of people with any mental issues, any disabilities. Very tolerant. Wonderful to them. Everyone was wonderful to my brother. The time we moved in.

Melinda: What was it like in the '60s?

Linda: You mean during the riots in Asbury?

Melinda: Well, in the '60s, you were 10 to 20, right? You were 10 in 1960, and you went to elementary school here.

Linda: I went to Ocean Grove. Then I went to the Junior High at the end of the street.

Melinda: And that was all Neptune included?

Linda: All Neptune was included. It was the first time we were integrated.

Melinda: What was that like?

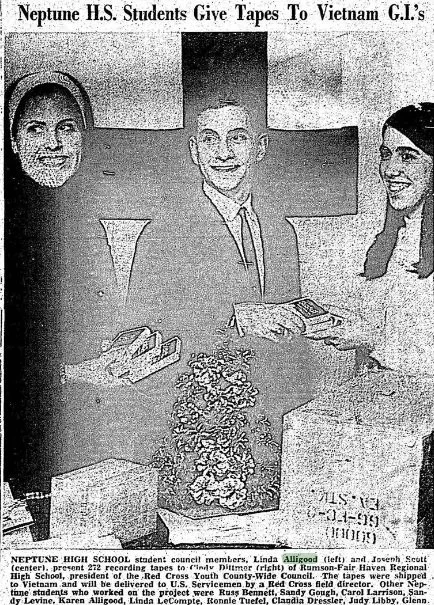

Linda: Well, I can give you a story previous to that. First of all, when we were in fifth grade, Betty Ann Risby was the first black child to come to Ocean Grove School because she lived across the street, across Main, but it was considered the Ocean Grove district. And the day she came to our class, The teacher had someone show Betty Ann all around the school while we all got a lecture on how Betty Ann Risby was a "Negro", and that we should be nice to her, which was nice. Some people, of course, didn't want to be nice to her. For many, she was a curiosity, which is why I still remember her name as Betty Ann Risby , because she was a curiosity. Ocean Grove was all white. Okay, there was another exception exceptions. There were other exceptions. The Sampler Inn, which I'm sure people have told you wonderful stories of the cafeteria here. The Sampler Inn, The Grand Atlantic, and the Homestead on the Boardwalk. As Karen and I, Karen is my twin sister, as we got older, we began to wonder what mentality brings the "Negroes" up on busses for the entire summer where they slept in bunks in the upstairs of the restaurants. They were brought in without family, and they, "Yes, ma'am", the "No Sir", the Ocean Grovers all summer. And Ocean Grovers, to this day, in fact, I was recently reading someone posted, they missed The Sampler Inn because of the black part of people who would carry your trays for you. They came in. Karen I, at a young age, called it the 'Plantations in Ocean Grove' because we could not understand why you brought up bus loads of black people to wait on white people for the whole summer. I think they got paid. But It was bizarre to grow up in a town when that happened. They weren't on the beaches. I don't think they were allowed on the beach until... Well, they just didn't go to the beach. But there was one beach that was 'the Black Beach'. That was the one between Asbury and Ocean Grove. You You never saw a black person on the Ocean Grove Beach. I'm not sure, but I think you had to own a home to get a badge. There was some reason you never saw any of the, quote, "Plantation People" on the beach. You never even saw them walking around the grove when they were not serving you. And the Ocean Grove people loved these guys, and they played right into it. I'm telling you, they would just man be "No Sir", this..

Melinda: You went to middle school, and then you went to the high school. Okay, but before middle school.

Linda: Am I talking too much about race, or is this what you want to hear?

Melinda: I want to know-

Linda: Because that's my perspective. I mean, that's probably issue with Ocean Grove. Don't get me wrong, I love the Ocean Grove. I loved growing up here, but I don't think I ever got over the racial divide here. When we were in Fifth or sixth grade, I think his name was Rayford, but I'm not positive, there was a young black kid who - my father had nailed a peach basket on a tree so that my brother could throw a basketball at it. He would come over every afternoon and play with my sister, me, and my brother. I could get choked up talking about this because he would play basketball with us every afternoon. Then one afternoon, my mother came out and said, 'The neighbors were upset because he was in our yard', and she told me I had to tell him, 'You can't come over anymore'. And I did. Oh, my God. Okay, so I'm getting a little choked up. I never forgot having to tell That kid, you can't play in our yard anymore because he was so good to my [brother]... We had fun every afternoon, and my brother was included. And though the Ocean Grove people were nice to my brother, he was never included in any activities. And I had to tell... I think his name was Rayford. I had to tell him, he can't come over anymore.

Melinda: Where was he from? And how did he-

Linda: Neptune. He was another one who was on the other side of Main, and he would come over. I think he was related to Betty-Ann, but I'm not betting on that, but in my memory, he would walk over from Neptune here because of my father putting the basketball hoop. And my parents had no problem with him being here, but the neighbors did. Said it didn't "look good", so he had to. He had to leave, and I had to tell him. Don't ask me why my mother made me tell him. That's a different story. Okay, go ahead.

Melinda: High school.

Linda: Yes.

Melinda: The Riots, '67.

Linda: Was that '67? [M: Mm-hmm]. Why am I thinking- '66? Why am I thinking closer on when I was in college? Because Tom who, who I married from Asbury Park, who, ironically, well, it wasn't ironic, but who was a black young man from Asbury Park, he was, at the time, I was seeing him, and he couldn't come to Ocean Grove, and I couldn't go to his house in Asbury. I mean, we were literally on the other side of the tracks. He knew if he came into Ocean Grove while there was rioting in Asbury, there would be major problems, police the whole bit. And I knew I couldn't over to Asbury because of those riots. I'm not sure about the '68 riots. Karen would probably remember. I know they existed, but it just seems to me it would... Oh, wait, wait a second. I graduated College in '72. This was in '68. Of course, it was in '68 this all happened. Oh, it was terrible. I would lay in bed at night and hear shooting in that and wonder if my... At the time, I didn't know he was going to... I was going to marry him, but I didn't know what was happening with his family. But I knew his family said, 'You cannot come into Asbury'. So, yeah, that was the '68 riots. I was thinking.

Melinda: What was the mood in Ocean Grove during all of that?

Linda: Very tense. Very, very tense. People walked-- there were rumors being spread that they were going to attack Ocean Grove. The riots were going to spill over. They were going to burn Ocean Grove. Blah, blah, blah, blah, None of which was ever true. We also had meetings, years earlier when they were going to integrate. I'm not going to get into that because I don't remember it so well. I just remember going to meetings where the Ocean Grovers were furious that their kids were going to have to mix with the kids from Neptune. I think that might have been for Junior High. But we met at the Dolphin on Main Avenue, and we had big meetings about it. Kind of like (in air quotes) "White citizen council meetings". We had meetings on why they didn't want us bused. I think they wanted Ocean Grovers to stay at Ocean Grove School until eighth grade. That's the story.

Melinda: What transition have you seen over the years here?

Linda: People don't know each other here anymore. Racially, it doesn't look that much different, tell you the truth. Though I don't think... There's several black homeowners now, and I don't think they get any grief at all. I wouldn't know, but I just don't think it's a problem. I actually married my husband in Ocean Grove Church. I was adamant this was my church, and I was going to get married here. My mother, because of the racial problems in that, my mother My mother had a reception here for me. She had been very scared when I started dating Tom because she felt they would lose their business, that Ocean Grove would turn against the dry cleaners that my father had, and that's it. Well, they didn't. She really didn't get that much grief as far as I remember. But when she had this... It was like a reception, a wedding reception for me. Afterward. A couple of Ocean Grovers, one who you know very well, came and not only... I mean, just bought me handmade gifts that they had spent months working on that was It was so beautiful. The man who gave the toast was a Jewish fellow who my family loved, whose wife had to put her name on the lease because when they bought the house, he was not allowed be on the lease. He toasted me and said, "Mazel tov". I always remember that. I thought, Robbie can't be on the lease, and here he is, [saying] "Mazel tov". And Tom and I celebrated. It was a It was a wonderful Ocean Grove experience. It was just like everybody who was in my corner was here. They made a point of being here.

Melinda: What year was that?

Linda: '79, [counting] 79... Was it '79? Yeah, I guess I got married around '78 or '79. Yeah. I mean, it was great. Can I say Marilyn? [M:Yeah]. Marilyn Shotwell on her sister. I mean, Marilyn made me the most beautiful painting for Tom and me. And her sister, embroidered a wedding announcement with both our names on it. I know. It was incredible. She had spent so much time on this. So it wasn't all of Ocean Grove. I don't know. There's another part of me that thinks my mother and father were so well-liked that maybe people said, 'Well, if they're okay, I'm okay'. I don't know. Today, what I see as a difference is we don't know each other. I mean, if you know the people on your block, you're lucky, but there will be no more walking home from school and having your teacher on your street or having someone I'm telling you, 'Get moving', another adult from another block. Everyone knew you. I mean, if you were fooling around on the way home or fighting with somebody or arguing or whatever, one of your neighbors stepped out and said, 'You don't want me to tell your parents, do you'? Well, first of all, there's no kids in Ocean Grove now. You hardly see a child. You see the money in Ocean Grove now is 100% different. Everybody was struggling back there but didn't know they were. We were all just everyone thought everyone had money because everybody was in the same bracket. Now, there's a huge divide on that one.

Melinda: How do you see that?

Linda: I don't see it as good... I think it's more that the money has bought them a summer home, so people aren't here and... When you're not here all year round, you don't know your neighbors. You don't look out for your neighbors as much. Everybody watched out for us. They watched out for my brother, but they always watched out for -- you know, we were always called the twins. To this day, someone will see me and say, "Oh, aren't you one of the twins?" Always watched out for us. You watched out for everybody else's kid. Everyone did. We knew every kid in the school, and we knew every Ocean Grover. It's just....But anyway.

Melinda: In the '90s, when we started to deinstitutionalize people from state facilities, how did that impact Ocean Grove?

Linda: It was terrible because greedy landlords opened - they turned their hotels, which they never made money off in the summer. They turned them into boarding homes because they could collect SSI checks 12 months out of the year. However, the people never had any supervision. During the day, Ocean Grove was like a ghost town with people released from a mental hospital and living in these unprotected boarding homes, roaming the streets. Then one day, a class trip, and I might get checked on this, but I'm pretty sure I'm right on this. A child on a class trip in Ocean Grove to one of the... I think it was [unintelligible], to tell you the truth. She got hit by one of the mentally ill people. That changed stuff. Then it was, We have to do something about this. One by one, they started shutting down the boarding homes. Though I don't know what happened to the people, I have a feeling they were sent to Asbury Park. They didn't stay in Ocean Grove anymore. When they closed down the boarding homes, you didn't see them walking the streets anymore. I'm curious where Ocean Grove took them to. Then the gay influx started. That was shortly after the boarding home closed. Gay people started moving into Ocean Grove, and that's when the tide turned. Everything became a little different. We've moved upscale, upscale, upscale since then, and more beautiful. But I think if I had my brothers, I prefer knowing people on my block. I I prefer people watching out for each other. We don't have that now.

Melinda: Any final thoughts?

Linda: What was a great town to grow up in? I'm telling you, you never... You could go by yourself. You had the freedom to go by yourself, to go to the beach. You never looked over your shoulder. You never had to. You were always watched by someone. That's my final thought. It was a great place to grow up. As I said, for a white Methodist child, you wouldn't get it better. You didn't get much better.

Melinda: Thank you.